Hypertension impairs blood vessels, neurons and white matter in the brain well before the condition causes a measurable rise in blood pressure, according to a new preclinical study from Weill Cornell Medicine investigators. The changes help explain why hypertension is a major risk factor for developing cognitive disorders, such as vascular cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease.

The preclinical study, published Nov. 14 in Neuron, reveals that hypertension may induce early gene expression changes in individual brain cells that could interfere with thinking and memory. The findings may lead to medications that both reduce blood pressure and prevent cognitive decline.

Dr. Constantino Iadecola

Patients with hypertension have a 1.2 to 1.5-fold higher risk of developing cognitive disorders than people without the condition, but exactly why is not understood. While many current hypertension medications successfully lower high blood pressure, they often show little or no effect on brain function. This suggests blood vessel changes could cause damage independently of the elevated pressure associated with hypertension.

“We found that the major cells responsible for cognitive impairment were affected just three days after inducing hypertension in mice—before blood pressure increased,” said senior author Dr. Costantino Iadecola, director of the Feil Family Brain and Mind Research Institute, professor of neuroscience and Anne Parrish Titzell Professor of Neurology at Weill Cornell Medicine. “The bottom line is something beyond the dysregulation of blood pressure is involved.” Dr. Anthony Pacholko, postdoctoral associate in neuroscience at Weill Cornell, co-led the work.

Aging Too Soon

In previous work, Dr. Iadecola’s team found that hypertension affects the function of neurons globally, but recent innovations in single-cell technologies have allowed them to zero in on what is happening in the different types of cells in the brain at the molecular level.

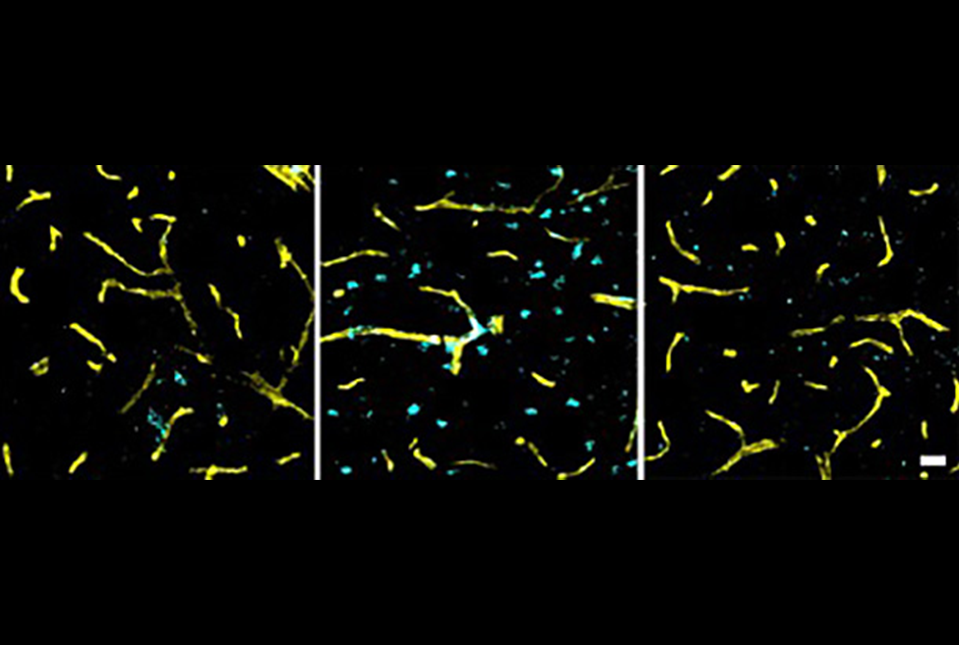

To induce hypertension in mice, the researchers administered the hormone angiotensin, which raises blood pressure, mimicking what happens in humans. Then, they looked at how different types of brain cells were impacted three days later (before blood pressure increased) and after 42 days (when blood pressure was high, and cognition was affected).

At day three, gene expression dramatically changed in three cell types: endothelial cells, interneurons and oligodendrocytes. Endothelial cells, which line the internal surface of blood vessels, aged prematurely with lower energy metabolism and senescence, indicating they stopped dividing. The researchers also observed early signs of a weakened blood-brain barrier, which regulates the influx of nutrients into the brain and keeps out harmful molecules.

Dr. Anthony Pacholko

Interneurons, brain cells that regulate nerve signals between motor and sensory neurons, were also damaged. This led to an imbalance between inhibitory and excitatory signals like that seen in Alzheimer’s disease. In addition, oligodendrocytes that enrobe nerve fibers with myelin did not properly express genes responsible for their maintenance and replacement. Without enough oligodendrocytes to maintain healthy myelin sheaths, neurons eventually lose the ability to communicate with each other, which is critical for cognitive function. Even more gene expression changes were observed at day 42, coinciding with cognitive decline.

“The extent of the early alterations induced by hypertension was quite surprising,” Dr. Pacholko said. “Understanding how hypertension affects the brain at the cellular and molecular levels during the earliest stages of the disease may aid in developing therapeutic strategies to combat the progression of neurodegeneration in people with hypertension."

Moving Forward

An anti-hypertensive drug already in clinical use called losartan inhibits the angiotensin receptor. “In some human studies, the data suggest that the angiotensin receptor inhibitors may be more beneficial to cognitive health than other drugs that lower blood pressure,” Dr. Iadecola said. In additional experiments, losartan reversed the early effects of hypertension on endothelial cells and interneurons in the mouse model.

“Hypertension is a leading cause of damage to the heart and the kidneys, that can be prevented by antihypertensive drugs. So independent of cognitive function, treating high blood pressure is a priority, no matter what,” Dr. Iadecola said.

Dr. Iadecola and his team are now investigating how the premature aging of small blood vessels induced by hypertension could trigger interneuron and oligodendrocyte defects. And in due time, the researchers hope to uncover the best way to prevent or reverse the devastating effects of hypertension on cognitive function.

Many Weill Cornell Medicine physicians and scientists maintain relationships and collaborate with external organizations to foster scientific innovation and provide expert guidance. The institution makes these disclosures public to ensure transparency. For this information, please see the profile for Dr. Costantino Iadecola.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health through grant numbers R01-NS095441 and R01-NS081179, the Alzheimer’s Association, the Cure Alzheimer’s Fund through grant number 243348 and the Feil Family Foundation.